Loving what you do……

Or perhaps that should read: ‘Hating what you can’t do, but are forced to do if you want to get paid’?

It may be a natural foible of the human condition that we dislike taking part in activities where we feel inadequate, weak or less able than our peers.

Professional performance that leads to praise, adulation and contemporaries clicking the ‘like’ button results in us wanting more of the same. Patients like the outcomes and we are happy. You’re a hero. This becomes a little addictive.

So, why would we want to revisit those dental techniques and specialties that leave us doubting our worth when we have a proven safe zone where we win more than we lose?

Actively dodging the stress-inducing task is the order of the day, week, month, and perhaps the foreseeable future.

I loved sprinting as a kid. I was big and strong and could cover a 100m in less time than the other boys in my school. When it came to 10-mile cross-country, however, I was too big…I was slow. I didn’t win. I didn’t like it. My conclusion: I like sprints; I don’t like cross-country. This mindset even led to tribal rivalry and acrimony between the big sprinters and the skinny marathon-running wannabes.

Being biggish and pretty fast meant a lack of natural skill didn’t hinder me gaining relative success on the rugby pitch too, but this same physical constitution led to bewilderment and shame on the football pitch. If I couldn’t use brute force, I had nothing.

Deciding which sports I loved and which I hated and dreaded became easy. Not surprisingly, my choices centred on those that would result in applause and adulation for my performance. I cannot imagine how horrid it must have been for the little skinny kids to be forced onto the rugby pitch by their parents or teachers (kids don’t yet have fully formed empathy systems, so we didn’t go easy on them at all).

We hate being obliged to do things that we are not very good at. We hate it.

Nothing has changed. And it never will.

Usually, we like doing what we are good at.

We are also less likely to make careless errors doing a task we love than one we don’t, so we get ever more biased as to what tasks we do and do not want to do.

Perhaps the biggest pariah in dental tasks is the Root Canal Treatment.

Sure, for some the allure of wire bending or forming endless charts with periodontal indices is too much to resist. Many others find teaching patients to remove plaque is the sum total of their life goals, but…I have lost count of the number of times I hear, ‘I don’t like Endo.’ The reasoning isn’t always clear at first.

Why don’t you like Endo?

Does the colour of Gutta-percha offend you?

Is the smell of hypochlorite too reminiscent of an over-chlorinated swimming pool from school?

Does the lack of nurse involvement mean their total disinterest and physically observable boredom disrupt the ‘mojo’?

Or, deep down, inside your head and inside your heart, do you dislike it because you know you aren’t very good at it?

We have defined competence in another blog linked here: I am competent when I am willing to perform any given task in an entirely transparent way being observed by any number of similar peers and experts who are free to comment on me.

The seemingly invisible and certainly impenetrable orifice, the canal shaped like a Cirque du Soleil contortionist’s spine, the drunken disco lights and random bleeps on the apex locator, the anticipation of failure … any and all of them combine to make endodontics a hateful task we dread. The derisory 3 UDA value attached to this impossible task is the icing on the cake.

The easy options appeal: refer or extract. Both amount to the same meta-decision: AVOID!

Is there another option that the right training could make available? The evidence is overwhelming here. Yes, there is.

Train and work hard at the training. If you do this you can become an extra-ordinary endodontist, or indeed any type of clinician or professional you wish.

So what is the evidence, and how do we get this good?

There are a few excellent sources of evidence we can explore.

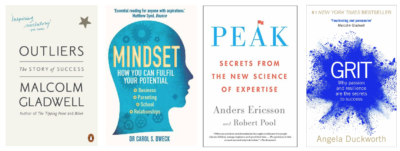

I cannot help but use the screen grab from amazon to capture them all!

There are four books below. All superb. All with similar themes, which can be used as templates for achieving excellence in dentistry (and almost any field) and help us enjoy and love what we do.

You should read all of these books if you are serious about enhancing your career. A mini summary is below:

– Deliberate practice with a purpose in mind is key to becoming an expert

– This practice should be carried out over enough time to achieve results

– Practise more outside your comfort zone with clear goals and measurable progress

– My goals should be well targeted in specific areas

– Each person will take a different journey to these long-term goals and progress at different speeds

– No matter what I want to tell myself — grit, hard work and determination are essential

– Whilst gaining knowledge is vital, it must go hand in hand with skills (this means that: whilst sitting listening to theory in lecture theatres or on my computer screen is very cheap to provide, this alone is an ineffective method of achieving our goals).

We must remain eternal students, never complacent in our learning.

I am known to often open a lecture by telling the audience: ‘Almost everything you have heard and are about to hear is wrong or out of date…or at least it will be soon, and perhaps one of you will make it so.’

Danger lies in arrogance about our perceived abundance of knowledge, as complacency may lead to stagnation and obsolete practice.

The wonderful Alexander Pope wrote in his famous poem “An Essay on Criticism”:

“A little learning is a dang’rous thing;

Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian spring:

There shallow draughts intoxicate the brain,

And drinking largely sobers us again.”

He was referring to the wellspring in Greek Mythology, sacred to the Muses, which was the metaphorical source of knowledge, art and science.

His words have been proven true by Anders Ericsson in his book Peak.

He summarises a lifelong body of research illustrating that being served up postgraduate education consisting of lectures and conferences, with a light sprinkle of hands-on training, is actually reducing our skills and abilities.

Although lectures have some value and need to remain, we must recognise their very significant limits. We need to be aware that gorging significant time on lectures — an imbalanced focus on theory — is likely to reduce our ability to help patients with new skills or techniques.

I believe it is the responsibility of lecturers to offer non-biased, objective summaries of relevant evidence so we can all share and absorb the salient information as efficiently as possible.

We then need to get those skills we all crave so much.

Perhaps we can refer to the top of the blog and revise the question about what we hate to do. List your hates and you may be listing the topics for skills you currently lack.

Now here is the really good news.

Talent isn’t a thing. It doesn’t exist.

Hard work, purposeful practice, honest feedback and enthusiasm will win over ‘talent’ every single time.

So here’s a plan (I hope it comes together for you):

Find individuals who are performing my desired skill, at a level that I wish to attain and then see if they have a well-structured programme that will help me learn from them (watching them lecture will not be enough and may actually make me worse).

Short hands-on courses are not enough; they may help identify my deficiencies, but I need as much repetition that I, as an individual learner, need. This may be more or less than others. A short course is very unlikely to offer me a true transfer of skills from the phantom head to the next patient.

I need a structured programme of purposeful, deliberate practice which focuses on the specifics of these skills and works to improve them with 100% honest feedback. Without this I will revert back to mediocrity or avoidance.

I must remember that my teacher went through a similar learning process and has carried out this procedure for real, perhaps over 1000 times. They are demonstrably competent.

Using a particular rotary system may be a bit of fun, but it won’t make me ‘an endodontist’. Buying a new composite will not teach me how to sculpt transitional line angles and make the composite look glass-hard and shiny.

I must also remember that my teachers do NOT have magic hands, nor have they read a magic book. They are the same as me, but they have learned, practised, understood and acted on the feedback. I can do the same.

I will NOT improve if I keep doing the same thing that I have always done. Think about a patient with moderate oral hygiene who is periodontally susceptible. They may say to you that they brush three times per day. But perhaps they are an ineffective tooth cleaner. Your feedback and advice may make them an expert…if they go home and practise, then come back seeking feedback, then practise more, then seek feedback…

Just ‘brushing harder’ wouldn’t have worked.

So, to sum up: When I have spent time with my teachers and they have transferred as many skills to me as possible, I must then practise these skills as much as I possibly can.

Our endodontics course is based on Anders Ericsson’s work. It is proven to give you these skills. It works. If you avoid Endo, struggle with any aspect of it, want to simply improve or — most salient of all — you dread it, sign up here.